PAULINE MICHELLE FERDINANDE GARCIA VIARDOT (1821-1910) is one of the most influential women in the classical music world of nineteenth century Europe. As a singer, her extraordinary opera career, marked by a prodigious talent and charisma on the stage, inspired dedications, premieres, and roles written specifically for her. Her music salon hosted many major composers of the time-Berlioz, Liszt, Chopin, Saint-Saëns, Meyerbeer, Brahms, and Wagner, to name a few, and allowed them to showcase and perfect their compositions. Frequently, she personally helped composers contract performances of their works, particularly operas. Throughout her career, Pauline worked as a composer, as well. Her art songs and operettas are often overlooked and rarely performed; yet a few of them represent musical gems that should not be forgotten. Particularly interesting are her transcriptions of Chopin mazurkas into solo songs and duets for voice. She worked hand in hand with the composer to transcribe twelve mazurkas, a relatively unknown but significant collaboration. It is important to look at the span of Pauline Viardot's life to see how her experiences as a performer, teacher, supporter of the arts, and composer influenced much of the operatic world of the nineteenth century.

Pauline Viardot, born in Paris on July 18, 1821, lived to be eighty-nine years old, passing away in the same city on May 18, 1910. Pauline was born into a family of remarkable musicians. Her father was Manuel Garcia, a famed voice pedagogue, composer, and Spanish tenor. Manuel Garcia is often confused with his namesake son, Pauline's brother. The younger Garcia, while also a singer, is best known for his invention of the laryngoscope, the Garcia Method of singing, and his publications on voice pedagogy. Viardot's mother, Maria Joaquina Stichès, was also a musical influence in her children's lives. She and Manuel pere met while she was singing opposite him at the Madrid opera company where he was the principal tenor.(1) Perhaps Pauline's most popular relative was her sister, Maria Malibran, the immensely famous opera soprano who died tragically at the age of twenty-eight.

Viardot was born into a world of music and seemingly had little choice but to embrace it. By age four, she accompanied her family to the United States, as her father led the first opera company to perform fully staged performances of Italian opera in New York-with him and his son as the baritones (Garcia pere was now assuming baritone roles) and daughter Maria as the prima donna.(2) Pauline was extremely gifted from a young age, and by eight years old she was already able to accompany singers on the piano in her father's voice studio.

She was a child of very marked musical abilities but also of exceptional intelligence of a general order. She had a desire to learn . . . She was able to appreciate her father's qualities without being irritated by his defects, and was consequently able to profit from his instruction and his influence to the full.(3)

Since her father passed away before Pauline had turned twelve, much of her vocal development was learned from listening to his lessons as a child. For the entirety of Pauline's career she used the exercises, canons, and arias composed by her father specifically for her voice.(4)

Pauline had developed into an incredible pianist and wanted to focus her career on the piano alone. Fitzlyon reminds us that "in fact, she remained an outstanding pianist all her life; Liszt, Mocheles, Adolphe Adam, Saint-Saëns, and many other distinguished musicians have left enthusiastic accounts of her playing, and some of Chopin's happiest moments were spent making music with her at Nohant."(5)

At the age of eight, she began her formal musical education, studying the piano with Meysenberg and Liszt, in addition to composition with Reicha. Although Pauline thought of herself mainly as a pianist, after her sister's death in 1836 her mother made her focus on her singing career.(6) Her mother, as well as the public, expected Pauline to carry on the Garcia tradition of great opera singers after Maria's death. Maria Malibran's husband, Charles de Bériot, was a well established violist, and at the age of sixteen, Pauline made her singing debut in Brussels by his side. Upon embarking on a concert tour in the spring of 1838, the public took note of her exceptional three octave range and ability to accompany herself on the piano.

The critic of the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung wrote: "Mademoiselle Pauline Garcia obtained in her first concert a remarkable success and was greeted with acclaim on her second appearance. Her ability is already very obvious (she is 17 years old), and her intonation is true and pure. We have not heard her sing any of her own songs yet but we believe that she is a talented composer."(7)

It was on this tour that Pauline first encountered Felix Mendelssohn. He had been a supporter of Maria Malibran and was astounded by the level of skill Pauline demonstrated at such a young age.(8) Mendelssohn introduced Pauline to Robert Schumann, who was courting the very young Clara Wieck at this time. Pauline and Clara would soon become friends and performed in many piano duets, private organ concerts and recitals together throughout their lives. Pauline admired Clara as a pianist, and Clara called Pauline "the most gifted woman I have ever known."(9)

Soon after her tour with Charles de Béroit, Pauline made her operatic debut as Desdemona in Rossini's Otello on May 9, 1839 in London. The following fall she was asked to sing the same role at the Paris Théâtre Italien, where she would meet her future husband, Louis Viardot, the director of the theater.(10) Pauline had great success at the Théâtre Italien, and she made many friendships in Paris, including the famous novelist George Sand.

George Sand was a divorcée feminist writer, who wore men's clothing and used a male pen name in order to establish her writing career.(11) Pauline and George Sand had a long lasting friendship, which greatly affected Pauline's life and career. Sand had written the title character of her novel Consuelo to reflect Pauline Viardot. She was also the one to suggest Pauline marry Louis Viardot. Pauline married Viardot in 1840, and though he was twenty-one years her senior, he was financially secure and thoroughly devoted to her. Sand also introduced Pauline to Frédéric Chopin, who was Sand's lover for most of her life.

In 1843, Pauline made her debut on the operatic stage of the Imperial Opera in St. Petersburg, Russia. Her operatic career blossomed as she led the return of Italian opera to Russia. Pauline sang in Russian premieres of Sonnambula and Lucia di Lammermoor, as well as in many other Italian operas. It was then that she began a friendship with Mikhail Ivanovitch Glinka. The pair had mutual respect for each other's work: she performed his songs and introduced them to French audiences; he became one of her avid supporters.(12) In St. Petersburg, where Russian audiences flocked to her performances, she became a sensation. Along with critical acclaim, Pauline began her controversial relationship with Ivan Turgenev. Turgenev fell in love with Pauline instantly, but she was accustomed to having many admirers and was not interested. He would become a close family friend and be part of the rest of her life. Countless sources discuss the relationship between Turgenev and Pauline Viardot; some refer to Pauline as his muse, others as his lover. In any case, it is noteworthy that Turgenev lived with Pauline and Louis Viardot for many years.

Thanks largely to Pauline's stardom in Russia, the Viardots purchased the Château de Courtavenel near Paris. The castle became one of the central places of artistic convention in France. Though they still resided in Paris, their summer home in Courtavenel was immensely popular. Pauline had the attic converted into a theater called the Théâtre des Pommes de Terre (Theater of Potatoes) because admission was one potato only.(13) Guests of the home included musicians Berlioz, Saint-Saëns, Franck, Rossini, and Weber; writers Charles Dickens, Emilie Augier, and Jules Simon; and painters Delacroix, Corot, Scheffer, and Doré.(14)

In 1844, Pauline returned to St. Petersburg to perform the incredibly difficult role of Norma. There she remained for two more seasons, before falling ill and leaving in February of 1846. Once she had recuperated, Pauline sang in Berlin under the direction of Meyerbeer and continued on to Dresden and Hamburg. Her repertoire was impressive, and she performed both previous roles and new roles in German (a simple task for a woman fluent in five languages since childhood).(15) It was during these years that Pauline faced competing opera divas, Giulia Grisi and Jenny Lind. All three sang similar roles, but Pauline's acting prowess prevailed over the equally talented singers. In addition to her operatic performances, Pauline had many concert engagements; especially notable were her performances at Covent Garden in this time. Interestingly, her most popular concert included her performance of two Chopin mazurkas, which she had arranged for voice, both virtuosic pieces with a huge range combining legato singing and chromatic coloratura.

Aside from Chopin, Pauline was close to other composers at this time, and particularly was a loyal friend to Hector Berlioz. In 1848, when he was conducting for Louis Jullien and Jullien's bankruptcy had robbed Berlioz of his pay, Berlioz himself fell into bankruptcy. He had to produce a concert on his own initiative in order to earn money. He invited all of his friends, including Pauline, to perform for no remuneration.(16) At this concert Berlioz created a new, expanded orchestral arrangement of his cantata La captive for Pauline, and was amazed with her interpretation.(17) Berlioz always praised Pauline and later wrote of a performance of Verdi's Le trouvère:

Mme. Viardot is a great musician . . . she unites an irrepressibly impetuous and imperious verve with a profound sensibility and with an almost deplorable faculty for expressing immense grief . . . she is one of the greatest artists in the history of music.(18)

Berlioz was always an avid supporter of Pauline and never failed to express his adoration for her dramatic and vocal prowess.

After singing to great acclaim in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots, Pauline finally began to work on the premiere of Le prophète-the role of Fidès written specifically for her by Meyerbeer. The first performance took place at the Paris Opéra on April 16, 1849, and it is now seen as the creation of the contralto as a leading role in an opera. She also sang the part in Italian at Covent Garden, and it became one of her most identifiable roles.(19)

That fall, a young Charles Gounod was sent to have an interview of sorts with Pauline. She was skeptical at first, but came to appreciate his extraordinary talent. She introduced him to writer Emilie Augier, who eventually wrote the libretto for Gounod's opera Sappho. Gounod came to Pauline after the death of his brother Urbain, while he was living with his ailing mother. He had fallen into a depression and his friendship with Pauline helped him continue to compose. Pauline praised Gounod's musical talent, and many sources, including both the Kendall-Davies and Fitzlyon biographies, imply an amorous affair. Fitzlyon dismisses most of the evidence of a romantic relationship as gossip caused by their deep musical connection;(20) however, Kendall-Davies goes into great detail describing their romantic relationship as the "greatest emotional crisis of her life . . . supposing that she had given birth to Gounod's child."(21) In the midst of the emotional turmoil of her secret relations with Gounod, and the birth of her daughter Claudie, the opera Sappho premiered on August 9, 1851 at Covent Garden. It was received with harsh criticism, and though Pauline's performance was praised, Gounod himself wrote to a friend that Pauline's singing career was at its end.(22)

Viardot had performed in both Paris and London during these years and returned to St. Petersburg in 1853 to sing the Russian premiere of Prophète. As in her previous trip to Russia, she sang to great applause, performing many roles and concerts. In January 1855, Pauline was visited by Giuseppe Verdi, who came to ask her to sing the role of Azucena in the new production of Il trovatore at the Paris Opéra, as the replacement for an ill Mme. Alboni.(23) Pauline not only learned the role in a few days, but after several performances in Paris she continued to sing the role at Covent Garden premiere in May.

After her Verdi debut, Pauline delivered her fourth and last child, Paul on July 20, 1857.(24) For the next few years Pauline performed in Warsaw and London. During the time of her performance of Don Giovanni at Drury Lane in London, she acquired an autograph score of that opera at an auction for the sum of 200 pounds.(25 )She sold a Rembrandt painting and several jewels just to get it, and the score became a shrine to Mozart at her salon. For the rest of the 1858 season, Pauline made her debut in Budapest with her dramatic performances of Norma, Rachel (from La juive by Fromental Halévy), and Fidès.

Pauline was obviously a respected musician at this time, and when she was asked to perform the role of Lady Macbeth in Verdi's opera she sent him her own transpositions for the role to be sung in her lower voice. In 1859 she was performing in the British premiere of Macbeth while also rehearsing Martha and Don Giovanni, and she often wrote that the stress of performing was beginning to wear at her.

Terrible day. I got over-fatigued. I had a concert in the morning and in the evening a rehearsal of Martha from 7pm to midnight. I generally have to assume the part of the stage-manager for the operas which I sing, being the only one who speaks English well, and have to serve as interpreter between all my comrades and the costumiers, machinists, choristers, supers, etc; it is far more fatiguing than singing and after four hours of work on the stage, I am worn out.(26)

During this busy professional time, Pauline sang the aria "Che faro" from Gluck's Orfeo at concert, which was heard by Berlioz. Berlioz was so moved by the performance that when he was asked to revise and restore the original version (which had been reworked from its 1762 original version in 1774 to change the role of Orpheus from castrato to tenor), he decided to do it with her in mind and cast the role of Orpheus as a mezzo soprano. While working on this transposition, he also was composing Les Troyens, and he had Pauline sing the first public performance of excerpts from this score on August 29, 1859.(27) Pauline helped Berlioz write the piano reduction of Les Troyens and often referred to the work as "our opera."(28) Berlioz's adaptation of Orfeo (called Orphée in French) premiered shortly after on November 18, 1859 at the Théâtre Lyrique with Viardot performing. Audiences marveled at her portrayal, and her good friend, Charles Dickens, declared: "a most extraordinary performance-pathetic in its highest degree, and full of quite sublime acting . . . I was disfigured with crying."(29)

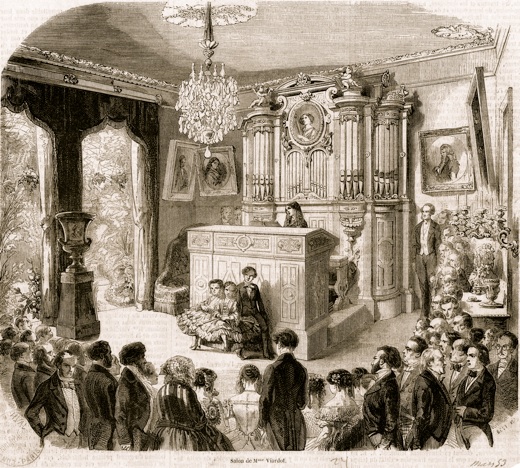

Pauline performed Orphée more than 150 times during her stay in Paris. At this time she also sang Beethoven's Fidelio and Gluck's Alceste, but none compared to her performance in Orphée. On April 24, 1863, Pauline gave her farewell performance; it was her official Parisian retirement-though she continued to appear in smaller opera companies for years to come, as well as concerts into the 1870s. Pauline and Louis Viardot left Paris to settle in Baden-Baden, Germany. It was here that she began her most famous music salon. The Viardot's Thursday night soirées attracted most of the well known composers of the time, as a place for trying out new works, making contacts, and socializing. Pauline, her family, and even Turgenev found life in Baden-Baden very enjoyable as she established their salon. The Viardot music salon affected a large number of important composers.

Another composer Pauline worked with in Baden-Baden was Johannes Brahms. He composed his expressive Alto Rhapsody, op. 53 for her, which she premiered on March 3, 1870.31 He also composed a serenade for her birthday and conducted it under her window, with her pupils performing.

Jules Massenet came to her when he was a young composer of about thirty, struggling to gain success, and with only a few works having been performed at this time. He became one of her "disciples" and brought his oratorio Marie Magdaleine to her salon. Drawn to the character, Pauline loved the work so much that she sang the title role at its premiere on Good Friday, April 11, 1873.32 This was one of her last public performances and the last new role she would ever perform in public -excluding roles she performed in her salon.

Camille Saint-Saëns had known Pauline since 1849, and they had a lifelong friendship. He dedicated his opera Samson et Dalila to her, for whom the part of Dalila was written. Unfortunately, it premiered after she had retired from the stage. While he wrote the opera in 1868, it was not performed until 1877 due to opposition to its biblical subject. Pauline set up a private performance of the first two acts of the opera in her home, starring herself and some students, accompanied by the composer himself on piano. Even in her old age, with waning vocal technique, Saint-Saëns admired her "performance of genius [which] made one forget both her age, which was unsuitable for Dalila, and the defects of her voice, and everything else . . ."(33)

Saint-Saëns brought Gabriel Fauré to the Viardot salon in 1872, where he would soon grow to love all the Viardot children as his own family. He was briefly engaged to daughter Marianne and dedicated many songs to each member of the Viardot family.(34)

Not only did Pauline help other composers, but she became a dedicated composer herself. She composed over 100 lieder and mélodies during her lifetime, most to be used as teaching tools for her own students. Many of her songs were published during her lifetime, the earliest collection being Album de Mme. Viardot, in 1843.(35) Her earliest compositions were usually vocal transcriptions of other composers' works, such as the mazurkas of Chopin. These generally featured a transparent texture, simplified harmonies, and a melodic vocal line. That is not to say they were simple to perform; she tended to compose for one with her vocal abilities, coloratura, and large range.

Pauline's relationship with Chopin is an important one, as are her transcriptions of his mazurkas. It seems that Pauline met Chopin at the end of 1839, when he was twenty-nine years old, and at the height of his musical career, yet already affected by the tuberculosis which was to cause his death ten years later.(36) He had a reserved, high-strung temperament that would eventually take its toll on his relationship with George Sand, yet when Sand introduced him to Pauline, their relationship was still strong. Fitzlyon's Viardot biography states that the idea of Viardot being Chopin's student is prevalent in her family today.(37 )There is no direct evidence of this, but it is known that they would often perform music together. In the Viardot salon they would read scores, Pauline might sing, Chopin might play, they might play duets -there is no doubt they enjoyed working with each other.

Between 1836 and 1842, Viardot published six transcriptions of Chopin mazurkas for voice and piano to the texts of Louis Pomey. They were most likely composed at Nohant and from Chopin's original manuscripts. It is known that the manuscript of Chopin's Mazurka in E Minor, op. 41, no. 2, was once in her possession, and therefore likely many others were as well.(38) Little is known about Louis Pomey and how his texts were chosen for the transcriptions. Five of the first six mazurkas were transcribed before Viardot met Chopin. "Seize ans" is the exception from the first group. An additional six were transcribed at a later date, and it is possible that Chopin had a hand in these transcriptions. All twelve mazurkas were published in France around 1880 and again in 1885 in Germany by Gebethner and Wolff.

Chopin had voiced his approval of these works after hearing Pauline perform them in Paris and London.(39) At Covent Garden on May 12, 1848 Pauline sang some of her transcriptions; they were received with great enthusiasm, and were encored. She sang them again at a concert with Chopin at Lord Falmouth's on July 12. Obviously Chopin approved highly of the transcriptions, as he invited her to sing them at his concert.(40) Jerome Rose says that Chopin's support of the transcriptions of his own works must have "represented an important accomplishment" for he was a "severe critic."(41) Chopin loved the publicity he received from her songs, and was apparently very offended to learn that she had left his name out of the billing of one concert in 1848. Jennifer Edwards states that "it is difficult to determine Pauline's reason for omitting his name. Chopin, however, clearly felt that Pauline was avoiding criticism from the press, for in a letter to a friend, he wrote of the 'pettiness' behind her doing such a thing."(42) Chopin felt she did this in her own best interest with regard to what he only referred to as a "certain" newspaper that had a particular dislike for his music. He never said which newspaper it was, but interestingly said a "certain" newspaper once wrote that "she performed songs 'by a certain M. Chopin' whom no one knows, and that she ought to sing something else."(43)

Pauline's later songs often consist of intricate piano writing and elaborate bel canto vocal cadenzas. Ard aptly describes her compositions as "dramatic and virtuosic, painting the musical atmosphere with the broad strokes of Bizet rather than the impressionism of Debussy."(44)

She also composed five salon operettas scored only for piano, which were mainly intended to be sung by her pupils and children. Turgenev wrote the librettos for the first three of her salon operas, and she wrote the libretti for the final two, Le conte de fées (1879) and Cendrillion (1904). Her first operetta, Trop de femmes, was composed in 1867 and became wildly popular among private audiences, so popular that the Queen of Prussia asked to see it performed.(45)

As word of her operettas spread, she followed with L'ogre, and the even more successful Le dernier sorcier. Le dernier sorcier was translated into German by Richard Pohl, and orchestrated by Lassen and partially by Liszt, so that it could be performed by professionals in Weimar in April 1869.(46) After this performance she was commissioned to write a full length three act opera by the Grand Duke of Weimar, but, owing to the Franco-Prussian War, the project was never realized. Pauline began composition of a few instrumental and choral works, but never had time to write works on a larger scale.

Pauline Viardot's life has been overlooked in musicological studies until only recently. As a woman with an amazing operatic career, she is often seen only as a mezzo soprano of remarkable range and dramatic ability. Pauline was much more than just a performer. Throughout her life she inspired a multitude of composers. Without her notable dramatic portrayals and vocal abilities, many of the works composed with her in mind may not have been written. Without her soirées, her musical patronage, and her connections, many famous operas we know today may not have been produced. Her compositions are perhaps the most overlooked aspect of her life, and they contain some great bel canto song repertoire that should be heard by modern audiences. Pauline Viardot was a multifaceted woman whose talents on stage and off inspired much nineteenth century music. She deserves to be recognized for her irreplaceable role in music history.

Author: Jesensky, Katherine LaPorta

Date published: January 1, 2011